The Mille Miglia was the original endurance rally. It ran for 24 years from 1927 to 1957 – Mussolini and then Hitler put things on hold for 6 years. The race was a 1500km loop from Brescia to Rome and back which is roughly 1000 roman miles. Some say it was created as a response to the Italian Grand Prix being moved to Monza but its hard to say what the Count Aymo Maggi and Franco Mazzotti had in mind when they started up the race so long ago.

The first year saw the race restricted to unmodified production cars. Bone stock from the factory. Its cool how the race evolved and the factories started building special cars but I love the that Mille was created for production cars. The course varied over the years including 12 other variations but that first year saw Giuseppe Morandi complete the course in just under 21 hours 5 minutes, averaging nearly 78 km/h (48 mph) in his 2-litre OM. Even cooler is that local Brescia based OM swept the top three places.

The stories from the early years are simply awesome. Take the 1930 Mille Miglia which Tazio Nuvolari won in an Alfa Romeo 6C. He started after his team-mate and rival Achille Varzi, but Nuvolari was leading the race on time. However he was still behind Varzi (holder of provisional second position) on the road. In the dim half-light of early dawn, Nuvolari tailed Varzi with his headlights off so Varzi couldnt see him in his rear-view mirrors. He then overtook Varzi on the straight roads approaching the finish at Brescia, by pulling alongside and flicking his headlights on as he went by! Nuvolari was awesome. Here he is racing in 1933:

The race was usually dominated by local Italian drivers and marques, but three races were won by foreign cars. The first one was in 1931, when German driver Rudolf Caracciola and riding mechanic Wilhelm Sebastian won with their big supercharged Mercedes-Benz SSKL, averaging for the first time more than 100 km/h (63 mph) in a Mille Miglia. Caracciola received very little support from the factory due to the economic crisis at that time in Germany. He didn’t even have enough mechanics to man all necessary service points so after performing a pit stop, his guys had to hurry across Italy, cutting they the middle of the course to arrive before the race car for the next pit stop. Imagine the party those guys had after winning like that!

1940 saw the debut of the first Enzo Ferrari-owned marque AAC (Auto Avio Costruzioni) with the Tipo 815, but it was the aerodynamically improved BMW 328 driven by Germans Huschke von Hanstein/Walter Bäumer that won the high-speed race with an all-time high average of 166 km/h (103 mph).

The Postwar Mille Miglia

The Italians continued to dominate their race after the war.

Mercedes made another good effort in 1952 with the underpowered Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Gullwing, scoring second with the German crew Karl Kling/Hans Klenk. The car was fast and went on to win the Carrera Panamericana that same year.Caracciola, in a comeback attempt, finished fourth. But there were very few non-Italians that did well in the 1950s; only Juan Manuel Fangio, Peter Collins and Wolfgang von Trips managed podium finishes.

Everyone focuses on Stirling Moss’s epic win but the reality was that Ferrari dominated this race in the post war era which started in 1947. Of the 11 final races, Ferrari won 8 of them only beaten by an Alfa in 1947, a Lancia D24 Spyder in 1954 driven by Ascari and of course the famous run by Stirling and Jenkins in their Mercedes in 1955.

In 1953 Shell commissioned this documentary which is simply amazing. Sports car racing on public roads was awesome. The ultimate tarmac rally.

Part 2:

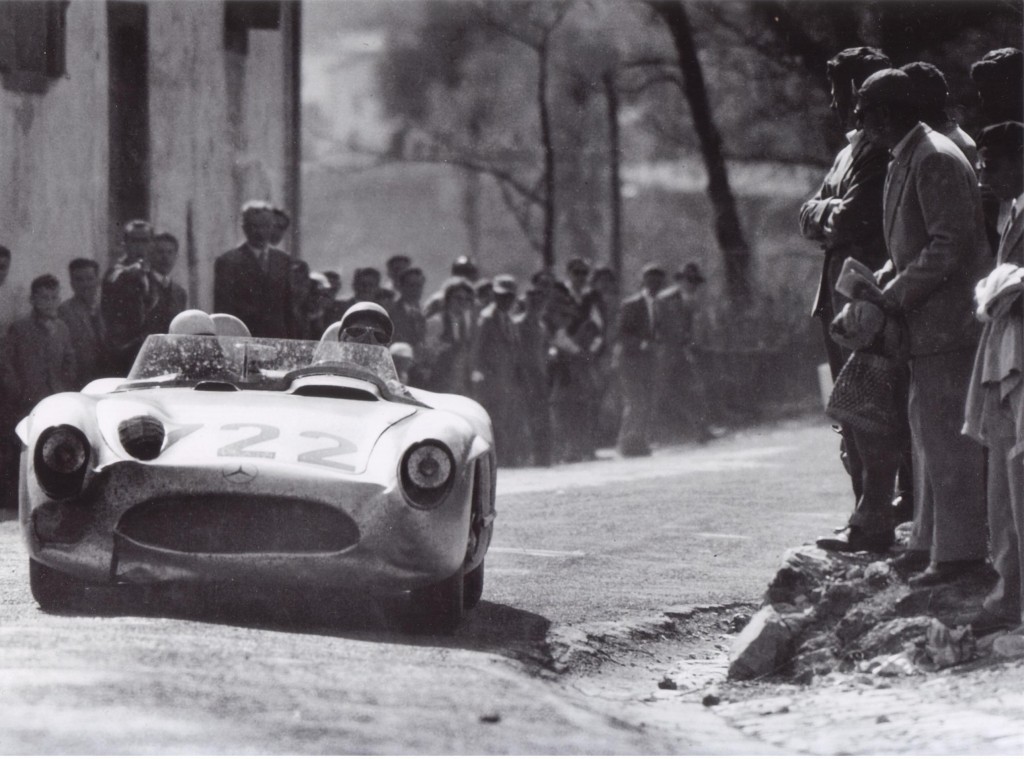

In 1955 Mercedes-Benz entered four 300 SLR’s which was based on the Formula One car (Mercedes-Benz W196) which was entirely different from their sports cars carrying the 300 SL name.

Both young German Hans Herrmann and Briton Stirling Moss relied on the support of navigators while Juan Manuel Fangio (car #658) preferred to drive alone as he had done since his co-pilot was killed in South America. Karl Kling also chose to drive alone, in the fourth Mercedes, #701.

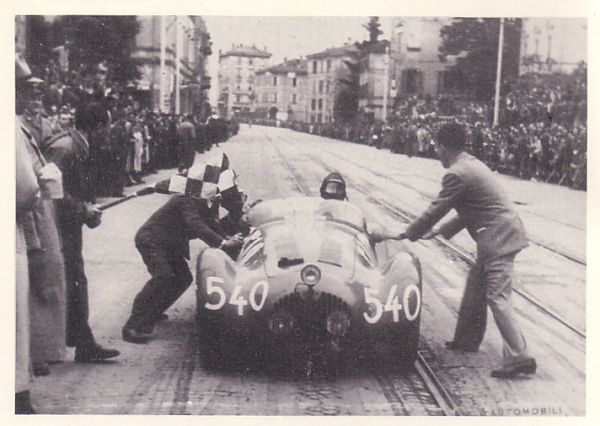

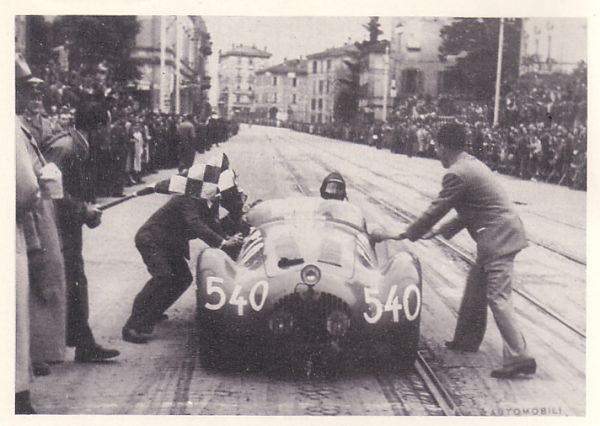

Similar to his teammates, Moss and his navigator, motor race journalist Denis Jenkinson, ran a total of six reconnaissance laps beforehand, enabling “Jenks” to make course notes (pace notes) on a scroll of paper which was 18 ft long. Jenkins would turn the roll revealing the next set of instructions with he delivered to Moss through 15 hand signals. Here is the start of the 1955 Mille Miglia. The cars looked awesome! Especially Fangio and Kling in their single seaters.

Even with the percents, Sterling wasn’t the fastest in the early hours of the race. Instead Car #704 with Hans Herrmann and Hermann Eger was leading the early stages. Herrmann great story was from 1954, where he ducked a railroad crossing gate the lowered right in front of him. He was driving a tiny Porsche 550 Spyder and Herrmann decided it was too late to brake anyway so he knocked on the back of the helmet of his navigator Herbert Linge to make him duck. A second later they slipped under the gates and barely made it across before the train. He was less lucky in 1955, when he had to abandon the race after a brake failure. Kling crashed at some point leaving Moss and Jenkins to lead the charge while Fangio finished second in the #658 car Pescara, about 30 minutes down after a fuel injection pipe had broken leaving him running on 7 cylinders.

After 10 hours, 7 minutes and 48 seconds, Moss/Jenkinson arrived in Brescia in their Mercedes-Benz 300 SLR with the now famous #722. They set the event record at an average of 157.650 km/h (97.96 mph) which was fastest ever on this 1,597 km (992 mi) variant of the course. This video shows Stirling Moss telling his story with scenes from the 1955 running of the race. It includes some pretty awesome quotes too. He also talks about why he loved racing. “Cause its dangerous… I race because I love racing. I raced because there are pretty girls around…” Told like a proper race car driver. He goes on to reflect on his short career saying “It was wonderful life…I can’t think of any like for any young man that is better than being a professional racing driver”

Keep in mind that while Stirling and Jenkins are considered to have the fastest record on the Mille, the BMW back in 1940 averaged a higher speed at 103mph but the course was different and the roads might have been straighter, faster. It’s just hard to say who was fastest when you change the race course. Stirling record would stand for the final two runnings of the race.

1956 was Eugenio Castellotti’s year in this beautiful Ferrari 290 MM Spider Scaglietti.

This might be one of the most beautiful Ferrari’s to ever race. At least of the front engined era of Ferraris.

Ferrari swept the first four spots in 1956, the year after Stirling’s epic win. The Mercedes team finished 5th, 6th, and 7th.

This video shows the final running of the proper Mille Miglia in 1957 and is the best of all the footage around:

The other part of the Mille that always seems left out is Jaguar. They were fast back in the 50’s and 60’s but somehow never won the Mille Miglia. Back in 1953 they entered this C-type wearing registration number ‘NDU 289′ that was driven by Mario Tadini and Franco Cortese. They also entered another C-type ‘KSF 182′ that was raced by Jimmy Stewart and later by Sir Jackie Stewart over a three-year period from 1953 to 1955.

Even more interesting is this C type entered in the 1952 Mille Miglia by Stirling Moss and Norman Dewis. Its looks awesome. But it wasn’t until Stirling switched to Mercedes that he finally won.

The D type was the car that should have done well or a special E type but I can’t seem to find any mention of these cars in the race. I know a D type was entered in Mille Miglia practice but it doesn’t appear to have entered the actual race.

The craziest of the Jaguar entries appears to be this 3400 Special entered by Clemente Biondetti and R. Cazzulani. They DNF’d unfortunately.

In 1954 George Abecassis (GB) Denis Jenkinson entered this HWM-Jaguar HWM 1, also a DNF. And yes its the same Jenkinson that went on to win with Stirling in 1955.

The End of an Era

From 1927 to 1957, the race took the lives of a total of 56 people. Eventually the race was banned like all other great races of the era because of fatal crashes. Racing is dangerous and even though the Mille claimed the lives of 56 people since its start in 1927, there were two big crashes which ended it forever. The first was the crash of a 4.2-litre Ferrari 335 S in 1957 that took the lives of the Spanish driver Alfonso de Portago, his co-driver/navigator Edmund Nelson, and nine spectators, at the village of Guidizzolo. The car supposedly landed on top of Portago and Nelson cutting them in half. The real problem was that five of the spectators killed were children, all of whom were standing along the race course. This video shows the start of the race and the actual wreckage of Portago. As a driver its difficult for me to watch. The wreckage is horrific.

They say the crash happened because the Portago desperately wanted to win this race and waited too long to make a tyre change and that the crash was caused by a worn tyre. The papers blamed Ferrari for the crash which ultimately lead to a lawsuit and criminal like investigation of the team. It was bad time for Ferrari and Enzo discussed stopping racing as a result of the public outcry. Eventually Ferrari was cleared of any wrongdoing and the team continued to race. But that wasn’t the only crash in ’57. A second car crash was in Brescia and took the life of Joseph Göttgens. He was driving a Triumph TR3. It was time for a change.

The Modern Mille Miglia – The “Parade”

From 1927 to 1957, the race took the lives of a total of 56 people. The race was reformatted and run from 1958 to 1961, but at road legal speeds with a few special stages driven at full speed. Then in 1977, the race was revived as the Mille Miglia Storica, a “parade” for pre-1957 cars that takes several days. There is some sort of Time Speed Distance Competition because they do announce a winner but Im quite sure how one wins. Hence the term parade. Its still a cool event but is now for rich guys in crazy race cars and journalists like Chris Harris in the video below or Ed Loh.

In 2007 a documentary film title Mille Miglia – The Spirit of a Legend was created honoring the legendary race.