Jaguar’s founding chairman, Sir William Lyons, understood that great styling and success in international racing sold cars. As such, the race to win, above all, was the gruelling 24 Hours of Le Mans. His phenomenal C-Type Jaguars, developed from the road going XK120, won Le Mans outright in 1951 and 1953. Jaguar was then under great pressure to come up with a new car to continue this record of success. The result was soon to become a legend. Late in 1953, Jaguar factory’s test driver, Norman Dewis, managed nearly 180 mph on the Jabbeke Highway in Belgium in a C/D-Type prototype, auguring well for the subsequent model D-Type’s chances in the seasons ahead.  Whilst the C-Type Jaguar employed a strong triangulated tubular chassis construction, the D-Type was built around an all-new, riveted aluminium-magnesium alloy monocoque designed by Jaguar’s chief designer and brilliant aerodynamicist, Malcom Sayer. Having spent time with the Bristol Aeroplane Company studying aeronautics, Sayer employed techniques evolved in the aviation industry to perfect his advanced method of monocoque construction. He was one of the first designers to apply the principles of aerodynamics to cars, coincidentally creating one of the most beautiful forms of the era. Sayer famously went on, of course, to design the legendary Jaguar E-Type. The D-Type was smaller, five inches shorter, and more svelte than a C-Type. The two-seat cockpit was permanently divided by a thin body panel that had a snug right-hand-side opening for the driver, with a smaller opening on the “passenger” side.

Whilst the C-Type Jaguar employed a strong triangulated tubular chassis construction, the D-Type was built around an all-new, riveted aluminium-magnesium alloy monocoque designed by Jaguar’s chief designer and brilliant aerodynamicist, Malcom Sayer. Having spent time with the Bristol Aeroplane Company studying aeronautics, Sayer employed techniques evolved in the aviation industry to perfect his advanced method of monocoque construction. He was one of the first designers to apply the principles of aerodynamics to cars, coincidentally creating one of the most beautiful forms of the era. Sayer famously went on, of course, to design the legendary Jaguar E-Type. The D-Type was smaller, five inches shorter, and more svelte than a C-Type. The two-seat cockpit was permanently divided by a thin body panel that had a snug right-hand-side opening for the driver, with a smaller opening on the “passenger” side.  A welded aluminium front sub-frame of square-section tubes, bolted to the monocoque, was used to mount the familiar seven main bearing, 3.4-litre Jaguar engine, which was now canted eight degrees from vertical to clear the low bonnet line. The adoption of dry-sump lubrication allowed the engine to drop a further three inches in the sub-frame to further reduce the frontal area. Equipped with three twin-choke Weber carburettors, the output was a healthy 250 horsepower.

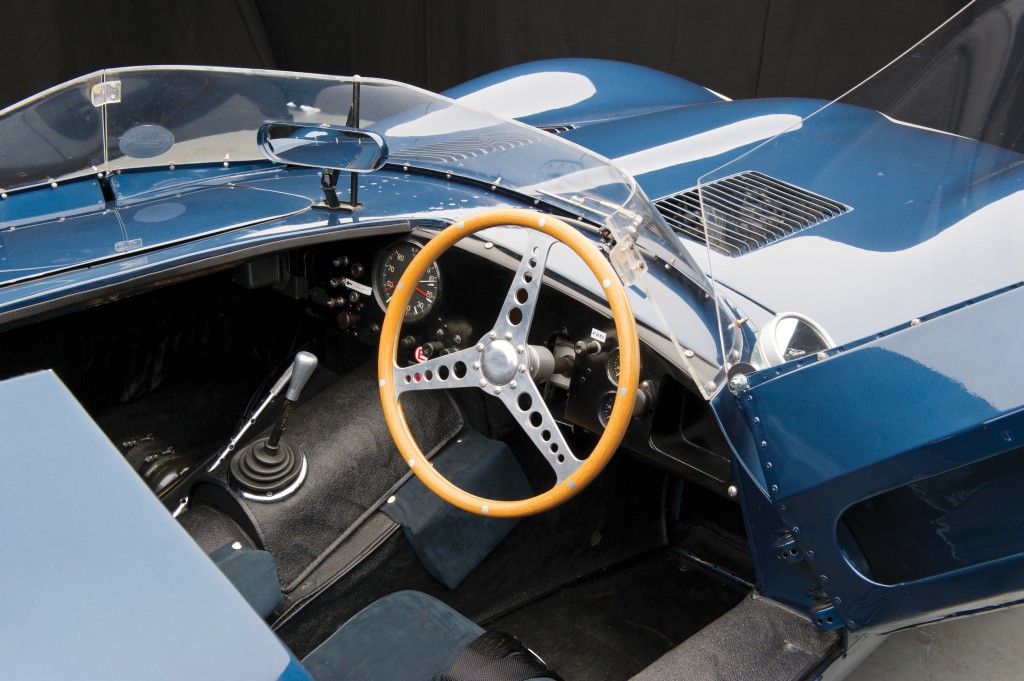

A welded aluminium front sub-frame of square-section tubes, bolted to the monocoque, was used to mount the familiar seven main bearing, 3.4-litre Jaguar engine, which was now canted eight degrees from vertical to clear the low bonnet line. The adoption of dry-sump lubrication allowed the engine to drop a further three inches in the sub-frame to further reduce the frontal area. Equipped with three twin-choke Weber carburettors, the output was a healthy 250 horsepower. Jaguar fitted its own, new, all-synchromesh, four-speed gearbox and utilised a three-plate clutch. Dunlop supplied not only the disc brakes, with multi piston callipers, but they also provided the stylish knock-off magnesium alloy wheels, which were drilled for lightness and brake cooling. The rack-and-pinion steering was based on the XK140 road car. Twin rubber fuel tanks in the rear were accessed via a quick-release filler cap that was incorporated in the driver’s faired headrest, to which a slim tailfin was riveted to ensure high-speed straight-line stability.

Jaguar fitted its own, new, all-synchromesh, four-speed gearbox and utilised a three-plate clutch. Dunlop supplied not only the disc brakes, with multi piston callipers, but they also provided the stylish knock-off magnesium alloy wheels, which were drilled for lightness and brake cooling. The rack-and-pinion steering was based on the XK140 road car. Twin rubber fuel tanks in the rear were accessed via a quick-release filler cap that was incorporated in the driver’s faired headrest, to which a slim tailfin was riveted to ensure high-speed straight-line stability.  Jaguar entered four D-Types at Le Mans for 1954. Three of the cars retired due to brake problems and engine issues, but not before Stirling Moss had managed 172.97 mph on the Mulsanne Straight. The Gonzalez/Trintignant 4.9 Ferrari 375 Plus, a much larger-engined car, was 12 mph slower. Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton, despite spending considerable time in the pits, finished just 105 seconds behind the winning Ferrari.

Jaguar entered four D-Types at Le Mans for 1954. Three of the cars retired due to brake problems and engine issues, but not before Stirling Moss had managed 172.97 mph on the Mulsanne Straight. The Gonzalez/Trintignant 4.9 Ferrari 375 Plus, a much larger-engined car, was 12 mph slower. Tony Rolt and Duncan Hamilton, despite spending considerable time in the pits, finished just 105 seconds behind the winning Ferrari.  One month later, at the 12 Hours of Reims, D-Types finished 1st and 2nd. For the 1955 racing season, the D-Type was much improved, with a brazed steel front sub-frame that, whilst stronger, was in fact a little lighter than the previous aluminium unit. Many structural improvements were made, and new “long-nose” bodywork, with prominent cooling ducts in the front, lengthened the car by 7.5 inches.

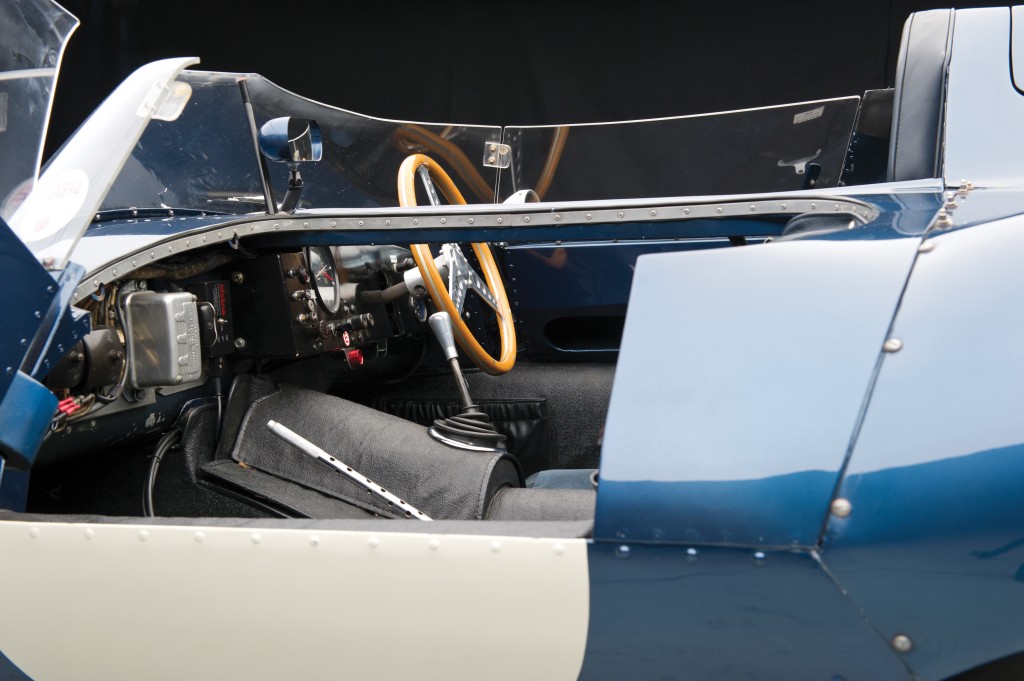

One month later, at the 12 Hours of Reims, D-Types finished 1st and 2nd. For the 1955 racing season, the D-Type was much improved, with a brazed steel front sub-frame that, whilst stronger, was in fact a little lighter than the previous aluminium unit. Many structural improvements were made, and new “long-nose” bodywork, with prominent cooling ducts in the front, lengthened the car by 7.5 inches.  The Works long-nose racers, such as the example offered today, were equipped with a wide wraparound windscreen that faired into the driver’s headrest, which itself was enhanced with a smoothly tapered fin that gracefully blended into the rear of the body. These body modifications by Sayer were intended to give improved penetration and stability, as well as better driver protection for the faster sections of the circuit, where speeds reached well in excess of 180 mph, which was incredible for 1955. The modified cockpit also gave the driver more elbow room and, therefore, a little more comfort, which was essential for endurance racing. Extensive cylinder head modifications increased power to 285 brake horsepower at 5,750 rpm for the Works cars.

The Works long-nose racers, such as the example offered today, were equipped with a wide wraparound windscreen that faired into the driver’s headrest, which itself was enhanced with a smoothly tapered fin that gracefully blended into the rear of the body. These body modifications by Sayer were intended to give improved penetration and stability, as well as better driver protection for the faster sections of the circuit, where speeds reached well in excess of 180 mph, which was incredible for 1955. The modified cockpit also gave the driver more elbow room and, therefore, a little more comfort, which was essential for endurance racing. Extensive cylinder head modifications increased power to 285 brake horsepower at 5,750 rpm for the Works cars.  The subject of this sale, XKD 504, was used as a test car for the prototype fuel-injection system, and it was subject to numerous engine changes whilst being run by the Works team. It was the spare car for the 1955 Le Mans race, which was the year of the worst accident in motor racing history, resulting in the withdrawal of the entire Mercedes-Benz team. Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb, in XKD 505, went on to win that ill-fated race.

The subject of this sale, XKD 504, was used as a test car for the prototype fuel-injection system, and it was subject to numerous engine changes whilst being run by the Works team. It was the spare car for the 1955 Le Mans race, which was the year of the worst accident in motor racing history, resulting in the withdrawal of the entire Mercedes-Benz team. Mike Hawthorn and Ivor Bueb, in XKD 505, went on to win that ill-fated race. XKD 504 went on to race in British racing green livery, wearing the Works trade plate number ‘164 WK’, at Silverstone in May 1956, with Jack Fairman at the wheel, and it then went on to the awe-inspiring Nürburgring 1000 km, where Frere and Hamilton was the driver pairing.

XKD 504 went on to race in British racing green livery, wearing the Works trade plate number ‘164 WK’, at Silverstone in May 1956, with Jack Fairman at the wheel, and it then went on to the awe-inspiring Nürburgring 1000 km, where Frere and Hamilton was the driver pairing. Jaguar built some 67 D-Types between 1955 and 1956. In their final year of production, and despite mixed results in European competition, the factory D-Types finished 1st, 2nd, and 3rd at Reims, where the overall winner, Duncan Hamilton, set a new lap record, after ignoring repeated pit signals that urged him to slow down.

Jaguar built some 67 D-Types between 1955 and 1956. In their final year of production, and despite mixed results in European competition, the factory D-Types finished 1st, 2nd, and 3rd at Reims, where the overall winner, Duncan Hamilton, set a new lap record, after ignoring repeated pit signals that urged him to slow down.

At Le Mans in 1956, the final year for the factory sports-racing team, and overcoming the bad luck that plagued the Works cars, leading privateer Ecurie Ecosse won the race. The team repeated that feat again in 1957, for a remarkable D-Type racing “hat trick”. The Scottish stable, founded by Edinburgh accountant David Murray, was one of the most successful privateer racing teams in history, and XKD 504 joined their competition line-up in October 1956.

For two years, the car was regularly campaigned by Ecurie Ecosse throughout Europe, sporting the Scuderia’s striking colours of Flag metallic blue with three white nose bands. XKD 504 ran at Spa and St. Etienne in the hands of Jock Lawrence, who claimed 2nd in the latter and finished 6th in the famous “Monzanapolis” event of 1957 at the Monza banked circuit, with Ninian Sanderson at the wheel. At the end of the 1957 season, following the tragic accident on the Mille Miglia, an FIA rule change to a 3.0-litre requirement ended the D-Type’s racing dominance.

However, in 1958, XKD 504 returned to Le Mans with a three-litre engine (number E 4007-10), wearing race number 7, and being driven by John Lawrence and Ninian Sanderson, but regrettably, it DNF. For its final Ecurie Ecosse outing, Masten Gregory and Innes Ireland competed at the Goodwood Tourist Trophy of 1958, where XKD 504 finished 4th.

In addition to the great success achieved in Europe, it should be noted that D-Types also competed very successfully in North America, with Briggs Cunningham’s cars winning at Watkins Glen three years in a row from 1955 to 1957.

XKD 504 continued its racing career in the hands of Mike Salmon, who won the Snetterton three-hour race in 1961, before being campaigned by legendary British privateer Peter Sutcliffe, whose virtuoso performances earned him the right to drive a Lightweight E-Type. Sutcliffe continued to race the car until an accident at Snetterton in 1963 (documented in Andrew Whyte’s Jaguar: Sports Racing and Works Competition Cars from 1954) ended its contemporary racing career. During the rebuild at the Jaguar factory, it was decided that the damaged front sub-frame would be replaced, as would have been normal practice in period. Jaguar already had the sub-frame from the 1955 Le Mans winner, XKD 505, which was available and fitted to 504.

Photo Credits: ©2014 Courtesy of RM Auctions